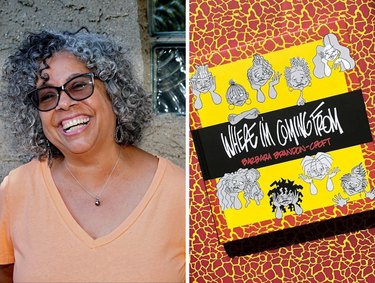

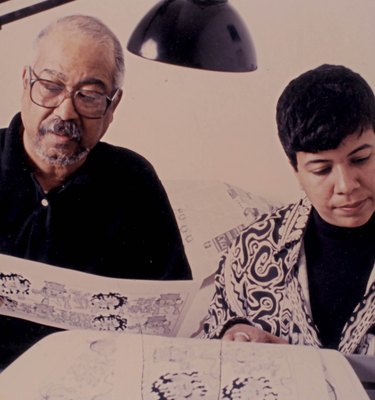

If you haven't heard of Barbara Brandon-Croft, allow us to introduce you. Her comic strip, Where I'm Coming From, was the first comic by a Black woman cartoonist to be published in nationally syndicated newspapers. She followed in the footsteps of her father, Brumsic Brandon, Jr., who wrote the iconic comic strip Luther. Together, they broke the comic color barrier as the first Black father-and-daughter duo to be nationally syndicated in different newspapers with different comic strips. Yes, that's a mouthful—but a meaningful one!

Barbara's strip is simultaneously humorous and political, mirroring what the country was experiencing during the comic's publication from the 1980s to early aughts. Where I'm Coming From stars Barbara's "girls," as she calls them: nine women who unapologetically speak their minds. Despite the time that's passed since original publication, much of the comic's content remains relatable, clever and entertaining.

Video of the Day

Video of the Day

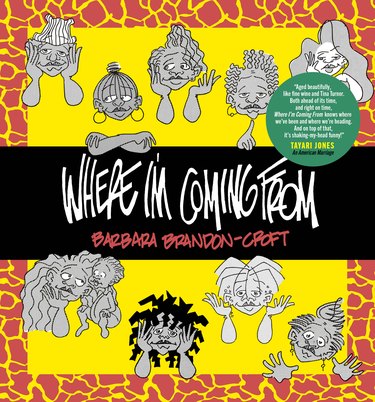

Now, after an almost 20-year hiatus, the "girls" are back to work in a new book from publisher Drawn & Quarterly also entitled Where I'm Coming From. It's a compilation of Barbara's iconic comic strips complete with beautiful illustrations, the meaty backstory of her journey, letters she received from newspaper publishers and other bits of her archive.

We sat down with Barbara to talk about this new chapter in her career—one that was completely unexpected yet graciously accepted.

What was your first professional cartooning gig?

BARBARA: In 1982, I went to Marie Brown, who was editor of Elan, a new magazine for Black women that was supposed to rival Essence. At the time, I had experience as a fashion reporter and illustrator, but I was prepared to do any job she'd hire me for. I brought my résumé and drawing portfolio to the interview. When she saw my drawings she said, "You're funny, you can draw—do you want to do a comic strip?"

I said yes, went home and thought out how I would do a comic strip for a Black magazine. It made sense to have the characters be Black women. I know of a cartoonist named Jules Feiffer who would sometimes have his comics talk directly to the reader and thought that was a good and direct way to communicate, so I adopted that style. When I returned to show Marie what I had come up with, she loved it and wanted to move forward. Unfortunately, the magazine folded before the first issue got a chance to run and I ended up working at Essence as a fashion and beauty director for five years!

How did you ultimately get your break in newspapers?

BARBARA: In the late 1980s, the Detroit Free Press did outreach to find diverse talent and, of course, they reached out to my dad. He gave me the letter and said, "Are you going to keep talking about being a cartoonist, or are you going to do it?" I said to him, "I'm going to do it" and sent them the strips I had done for Elan years earlier. They liked my work and wanted to work with me! So I said, "Essence, I'm outta here, I'm going to be a cartoonist," and put in my resignation. In 1991, Universal Press reached out and offered me a development contract. I got into two newspapers in the middle of the country. That was huge!

Besides your father, were there any other cartoonists who paved the way for you?

BARBARA: Jackie Ormes was in the newspapers before me—almost 80 years ago—in the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier, which were considered the Black press. It would be challenging to find a lot of people in media who even know anything about the Black press, but it was huge. She deserves her roses. She was great. I just happened to cross the color line. But it isn't lost on me that there wasn't another Black cartoonist in the mainstream—and I use mainstream as a euphemism for the white press.

What did you do when your comic strip ended?

BARBARA: My syndication ended in 2005 while I was freelancing at Parents magazine. By 2007, I became a full-time employee at the brand as their research director. A year or two later, I got a call from Tara Nakashima Donahue, whose parents owned an art gallery in New York called Medialia. She said she was doing an exhibit about female artists and asked if I would like to be a part of it. Since I hadn't been cartooning for a while, I told her I didn't have anything to show. She said, "Well, we can show some of your old stuff." We ended up doing a show entitled Still Racism in America: A Retrospective in Cartoons that showcased work from both my dad and me.

Has your work led to any surprising opportunities?

BARBARA: Thanks to Tara, I was introduced to the Women in Comics Collective (WinC) and they started inviting me to be on various Comic Con panels. It was big when I was a part of New York Comic Con. My son, who was in his late teens at the time, was so impressed! I was always resistant to be on panels because I wasn't sure I'd fit in. At one Comic Con, an audience member asked how they could see all of the panelists' work. Everyone had a website or a book; I didn't have either. When it was my turn to answer, I was like, "Um, well, if you're ever in D.C., you can go to the Library of Congress. My work is there." There was a hush over the room, and people were like, "Oh!" That was exciting and fun. So I did fit in.

Tell us about your book project. Where did the idea come from?

BARBARA: In 2019, I happened to see a message on Facebook—you know, one of those random messages from someone who's not your Facebook friend? It was from Peggy Burns, the top dog at publisher Drawn & Quarterly. She apologized for reaching out on Facebook—I still didn't have a website—and said she'd really like to do a collection of my strips. She knew my work and my characters very well, and we really hit it off. She also knew my father's work! She said, "You've made history, and it would be a shame if there wasn't a collection of your strips in a book." I couldn't visualize a book. She said, "Let me show you what we do."

She sent me great books they had done by Linda Barry, Ebony Flowers...all these award-winning people. They were the real deal. Once I agreed, she said, "We're probably going to need an agent." I was like, "An agent?!" I was on an unimaginable path—this is not the way things usually happen. I was calling these agents, and they were trying to sell themselves to me! People knew my stuff. I didn't have to explain myself to them.

What has the book process been like?

BARBARA: It's a brand-new experience for me. Early on, friends would ask me what the book was going to look like and I'd say, "I don't know!" I'm not nearly as organized at home as I was at work, so going through boxes of old materials and drawings was kind of wild. I didn't know how they were going to put this book together, so I just kept sending them stuff and they'd say, "Send more!" But I love how the book has turned out, and I hope it delivers what the publisher intended.

It's a piece of history and can be a teaching tool. Rebecca Wonzo, professor and chair of the Department of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, even wrote a long essay in the book that puts my work into context on a cultural level, and I'm very grateful for that. This can be a book for people who are teaching about comic history, Black people in comics, women in comics—it's the whole deal.

What are your thoughts on banning books and, thus, Black voices?

BARBARA: I think it's absurd. It's taking us back in time and makes me worry we never really left that time. The only way this country is going to learn to heal is to face the facts and understand that Black history is American history—you cannot exclude us from this nation. The idea that learning the truth about history will make kids feel bad is projecting. Kids want to learn. What do they know of color? They love each other, and facts are facts. We're going to stay on this same hamster wheel of getting nowhere if we don't try to learn, understand and teach.

Speaking of history, how does it feel to be a part of it?

BARBARA: My dad and I are very likely the only nationally syndicated father-and-daughter cartoonists. Ordinarily, a parent passes down a strip to their child. But my dad and I did it independently, in different syndicates and different strips. That's pretty phenomenal. I'm proud of that.